Aspect Ratios in Film and Video

(Excerpted from my Questions & Answers about the DTV Transition)

The relationship of the width of an image to its height is known as aspect ratio. The first television standards adopted the aspect ratio common to most motion picture films of 4:3 (or 1.33:1, although the actual Academy ratio is 1.37:1). As television began to gain popularity in the 1950s, motion picture studios looking for a competitive advantage began exploring technical differences and gimmicks, such as multi-channel sound, 3-D movies and different aspect ratios, which are commonly referred to today as widescreen. These aspect ratios presented the motion pictures in a dramatically different "frame" - much wider than tall. Directors and cinematographers exploited these new formats by shooting broad vistas (appropriate for the Westerns of the time) and by putting actors at the opposite ends of the frame.

The relationship of the width of an image to its height is known as aspect ratio. The first television standards adopted the aspect ratio common to most motion picture films of 4:3 (or 1.33:1, although the actual Academy ratio is 1.37:1). As television began to gain popularity in the 1950s, motion picture studios looking for a competitive advantage began exploring technical differences and gimmicks, such as multi-channel sound, 3-D movies and different aspect ratios, which are commonly referred to today as widescreen. These aspect ratios presented the motion pictures in a dramatically different "frame" - much wider than tall. Directors and cinematographers exploited these new formats by shooting broad vistas (appropriate for the Westerns of the time) and by putting actors at the opposite ends of the frame.

Though many proprietary aspect ratios were created and used over the years, only a few remain typical for contemporary motion picture production: 1.85:1, 2.35:1 and 2.40:1.

Historically, when these widescreen productions are broadcast on television, there are two general solutions to compensating for the difference in their aspect ratio and television's, letterboxing and "pan & scan." With letterboxing, the entire image as photographed by the motion picture crew is visible, but black or grey bars appear above and below the movie raster. Pan & scan attempts to fill the television screen by showing only a 4:3 portion of the widescreen image, losing some part of the content on the left and/or right.

Both solutions have their negatives:

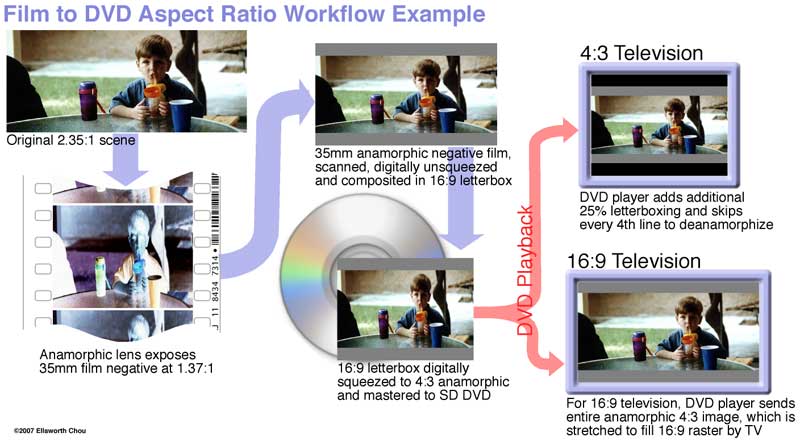

There will be a significant period of time of transition during which citizens will continue to use legacy 4:3 televisions - perhaps decades. Likewise, all television productions - particularly those shot on video - will remain forever in their original 4:3 aspect ratio (though some broadcasters mercilessly stretch or zoom these products to avoid or diminish dreaded "bars" on the tops or sides of viewers' TVs). Current standard-def commercial movie DVDs of widescreen movies are recorded anamorphically on the DVD, using every possible pixel represented by the 1:33 standard by first transferring the movie from film to video at 16:9 with some letterboxing. Then the movie is squeezed to fill the 4:3 raster of standard-definition video which DVDs record - this squashed image is an anamorphic image - meaning it is distorted horizontally, which is how some cameras and projectors capture and project 2.40:1 imagery on a 1.37:1 piece of 35mm film. Consumers tell their DVD players whether their televisions are 4:3 or 16:9. When the movie is played back on a 16:9 television, the DVD player knows to send the entire anamorphic image to the television, which is also configured to stretch the image to its original 16:9 shape. If the consumer has a 4:3 TV (here's the trick), the DVD player displays the black top letterbox bar, then simply skips every fourth line of video of the anamorphic image, finally drawing the bottom black bar. The resulting image is de-anamorphicized image. In reality, this image represents a strange kind of distortion, where each 3-line group is actually still anamorphic - distended vertically 25 per cent, but since there are only 360 possible horizontal lines of visual information (as little as 266 lines for a 2.40:1 movie), this is hard to perceive.